[ad_1]

Late 20th-century Vietnamese history casts a trancelike spell across Truong Minh Quy‘s “Viet and Nam,” a thickly shadowed exploration – or should that be excavation? — of national trauma and its habit of living on, in spectral form, through subsequent generations. Given an edge of radical newness by its frank, grimily beautiful portrayal of gay lovemaking (seldom have the body-contouring properties of coal dust on sweat-slicked skin been more sensuously explored), still, the rhythms of Truong’s film are slow, and the curtains-drawn darkness of much of its 16mm imagery may induce a state of meandering, semi-directed sleepiness. But then perhaps Truong does not mean us to watch “Viet and Nam” so much as he wants us doze and dream our way in and out of it.

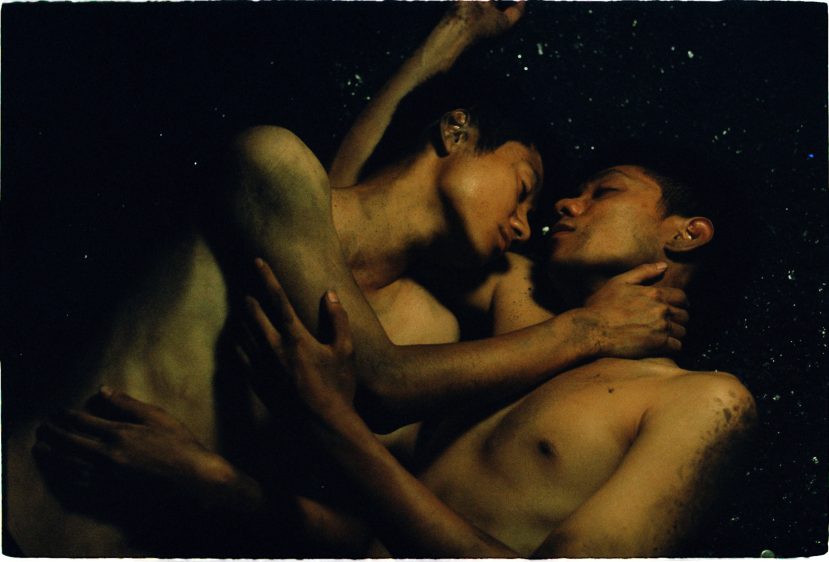

It is 2001 and Nam (Pham Thanh Hai) and Viet (Dao Duy Bao Dinh) — never distinctly identified as such within the film and given a joint “Nam/Viet” credit in the closing scroll — are two young coalminers in rural Vietnam involved in a tender but illicit relationship. Deep underground, in the sepulchral privacy of a nook carved out from the mine walls, they make love and cradle each other, anthracite sparkling around them like starlight. Son Doan’s subterranean, homesick, black-and-blue cinematography can be so shadowy as to be all but impenetrable, but sometimes out of the murk emerge frames of breathtaking loveliness.

Nam is intending to smuggle himself out of Vietnam, taking a perilous route involving a shady broker, a shipping container and a river crossing wrapped in a plastic shroud. Viet fears for him and wants him to stay, yet is also achingly resigned to his leaving. But before Nam goes, there are mysteries that need solving right here, chief among them the fate of his long-dead father, a soldier who might not have even been aware that he had a baby son at the time of his death. Along with his mother Hoa (Nguyen Thi Nga) and Ba (Le Viet Tung), a military veteran who may know where Nam’s father fell in battle, Nam and Viet go on an expedition toward the Cambodian border, in the slim hope of finding the dead man’s remains, guided mostly by Hoa’s dreams of her revenant husband and Ba’s hazy, possibly guilt-ridden memories.

They are far from the only family to have embarked on such a pilgrimage. Television news broadcasts list missing “martyrs” whose kin are begging for information that might help them locate their loved ones’ bodies. And Nam’s party encounters another group, who have engaged the services of a psychic (Khanh Ngan) in white face paint and a pink silk robe, who may be a charlatan but claims, un-disprovably, that the clumps of clay she claws out of the ground are in fact the sought-after man’s flesh, “turned into black dirt.”

Dead men turn into dirt. Dirt is compressed into coal. Coal is mined and burned and turned into smoke that acidifies the rain that floods the caverns and swells the rivers, drowning the unlucky and soaking through the market goods Hoa sells for her meager living. “Viet and Nam” has an environmental aspect that has less to do with the circle of life than the inexorable circle of death, in which the occasional moments of levity — Nam giving Viet a birthday cake or tenderly preparing the mosquito net around Hoa’s bed — barely provide a pinprick of light in the gloom. Truong’s approach is ostensibly similar to that of Thai master Apichtpong Weerasethakul and of last year’s Vietnamese Camera d’Or winner “Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell.” But while those touchpoints achieve a kind of transcendent lightness, “Viet and Nam” is constantly pulled down at the edges, made heavy with foreboding and waterlogged with generational sorrow.

Apichatpong, especially, likes to infuse his dreamscapes with the idea of the dead walking and talking, co-existing amongst the living. Truong, by contrast, is endlessly preoccupied with how the living, even when planning for the future or experiencing the joys and passions of the present, are forever being lured into joining the dead. It means “Viet and Nam” makes demands on even the most patient of viewers if they’re in any way resistant to the hypnotizing effect of its difficult, doom-laden atmospherics. But it does exert a powerful — if not exactly cheerful — gravity on those who can give themselves over to its persuasively pessimistic view of a national history that even this young, vigorous, loving pair can only stay on top of for so long, before it engulfs them, and pulls them down, under the sea or under the soil, into the clammy embrace of the past.