[ad_1]

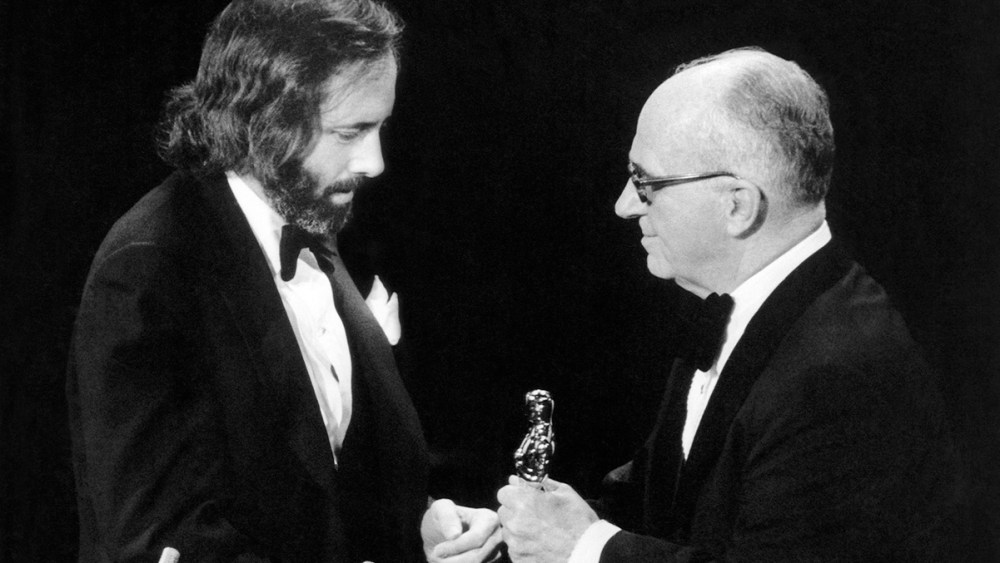

A great ending can be the hardest thing for a writer. For Robert Towne — who died Tuesday, having written and reshaped some of the most important films of the 1970s — finding the best way to wrap up a film was a career-long challenge. In the script that earned him an Oscar, the downbeat “Forget it, Jake — it’s Chinatown” finale was famously Roman Polanski’s idea.

And yet, there’s undeniable poetry in Towne’s passing: The Oscar winner died 50 years (and two weeks) after “Chinatown” opened, basking in the fresh round of appreciation that the half-century anniversary brought. Towne was a natural raconteur whose stories were every bit as rich as his screenplays — as evidenced by an in-depth Variety interview that ran last month — and whose best writing often went uncredited.

For those who weren’t around to have witnessed Towne’s transformative impact on American cinema in the 1970s, it’s fair to say that he brought reality to an industry built on fantasy. That didn’t stop him from later going on to work on the first two “Mission: Impossible” movies, but his instinct was to make films that reflected the world he knew — to write characters who swore (“The Last Detail”) and stumbled (“Chinatown”) and seduced (“Shampoo”) the way real people did.

For many, those three films, released within 14 months’ time, encapsulate Towne’s talent, representing a clear-eyed critique of American culture at a time of moral and political turbulence.

In “The Last Detail,” sailors sound like actual sailors — which is to say, they curse up a storm — even as they push back against a system that values obedience above all. (Years later, Towne’s longtime friend Jack Nicholson would bellow “You can’t handle the truth!” in “A Few Good Men,” though the line could just as easily have been the tagline for the brutally honest Hal Ashby film.)

The movie might not have taken place in Vietnam, but it was indirectly about that war, just as 1930s-set “Chinatown” used a decades-old case of institutional corruption to indict the greed Towne observed in his backyard (specifically, shady developers attempting to steamroll his corner of Benedict Canyon). Where earlier studio films noirs had often pinned the blame on lone offenders and femmes fatales, Towne indicted the entire system. And because the film is confined entirely to Jake’s experience, the audience discovers the extent of the betrayal at the same time the character does, sharing in his shock.

Opening in the wake of Watergate, “Shampoo” wasn’t as well-regarded upon release as it is today, possibly because Towne and co-writer/star Warren Beatty tempered the feather-light sex farce (about a straight hairdresser who’s sleeping with half his clients) with a timely skewering of the presidential election. For nearly two hours, Beatty’s character gets all the girls, but in the end, when the classic formula would have called for love to conquer all, the hairdresser watches Julie Christie drive off with her Nixon-like beau.

Towne was central enough to the New Hollywood scene that Peter Biskind dredges up loads of spiteful gossip about him in the book “Easy Riders, Raging Bulls.” Rather than repeat it here, what carries the ring of truth are reports that Towne became known for writing sprawling 250-page scripts (double what a typical feature required). In Sam Wasson’s “The Big Goodbye,” the film historian states that a draft of “Chinatown” came in at 180 pages.

Here was a talent who could size up other people’s screenplays and offer suggestions that immeasurably improved the end result, as he did as an uncredited script doctor on both “Bonnie and Clyde” and “The Godfather.” But when it came to his own work, he piled on the ideas, reaching toward a kind of impossible perfectionism. The resulting movies — including those he directed, such as “Personal Best” and “Without Limits” — demonstrate that those scripts could be whittled down and shaped into rock-solid motion pictures, which is ultimately what matters.

Towne repeatedly collaborated with three Hollywood megastars over his career — Jack Nicholson, Warren Beatty and Tom Cruise — recognizing what each of them could do for a role. With Nicholson (whom he met when the actor was an assistant for Hanna Barbera), Towne tapped into the actor’s capacity to play combustible, indignant characters, even going so far as to write a “Chinatown” sequel for Nicholson to direct with “The Two Jakes.” According to Towne, Beatty was incredibly self-conscious about the effect his physical beauty had on audiences, and so he called on Towne repeatedly over the years (on “Heaven Can Wait,” “Reds” and “Love Affair”) to help ground his characters. Impressed with Towne’s work on “Days of Thunder,” Tom Cruise came to trust the writer to help shape films to his driven, hyper-confident screen persona. The determination of “The Firm” and the first two “Mission: Impossible” movies is largely Towne’s doing.

Over the decades, Towne continued to work on other people’s scripts, while developing a handful of passion projects on his own. One, an unconventional Tarzan project called “Greystoke,” he imagined as being told largely without dialogue — meaning that most of the film would silently focus on how a human boy might have been raised by apes. Towne realized that he would have to helm “Greystoke” himself in order for his vision to work, taking on female-focused track drama “Personal Best” as a way of proving himself as a director.

The plan backfired: “Personal Best” was a challenge to make (hampered by legal woes and an actors’ strike), to the extent that he wound up surrendering his “Greystoke” script to Warner Bros. in order to get the film completed. Towne was devastated by what became of “Greystoke,” ultimately taking his name off the script and replacing it with his dog’s.

In the end, Towne worked on more films where his name doesn’t appear than those where it does. But his impact on Hollywood is hardly a secret. Towne wanted his characters to be as nuanced and multi-dimensional as real people, bringing complexity and thoroughly researched texture to the spheres they inhabited. Other writers admired the density with which Towne constructed worlds, and raised their game. Some, like Francis Ford Coppola (who cited Towne in his acceptance speech for “The Godfather”), have acknowledged his influence directly — even if credit didn’t seem nearly as important to Towne as making the best possible film.