[ad_1]

In more than a dozen states, doctors and nurses have resorted to paper and handwritten treatment orders to chart patient illnesses and track them, unable to access the detailed medical histories that have long been available only through computerized records.

Patients have waited for long stints in emergency rooms, and their treatments have been delayed while lab results and readings from machines like M.R.I.s are ferried through makeshift efforts lacking the speed of electronic uploads.

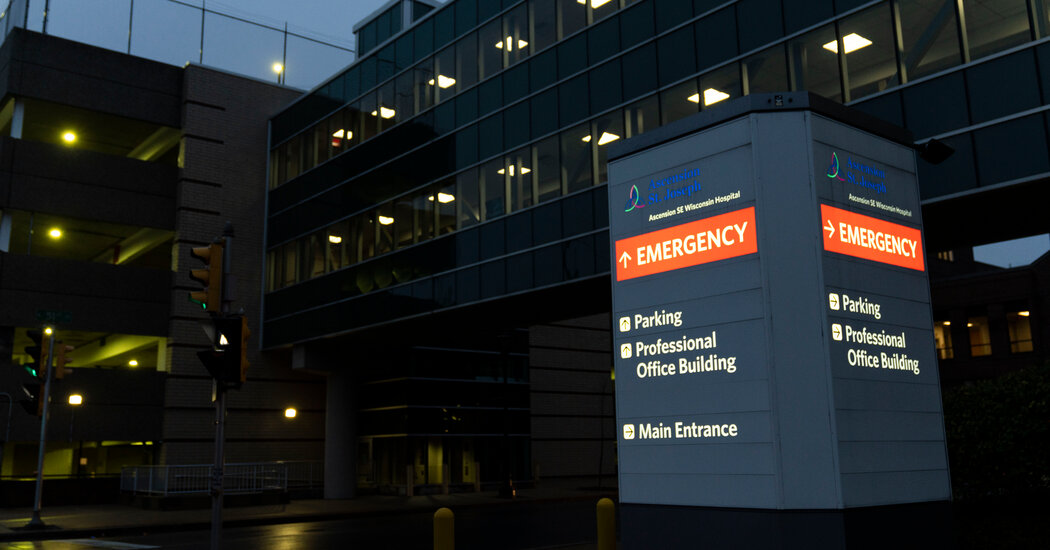

For more than two weeks, thousands of medical personnel have turned to manual methods after a cyberattack on Ascension, one of the nation’s largest health systems with about 140 hospitals in 19 states and the District of Columbia.

The large-scale attack on May 8 was eerily reminiscent of the hack of Change Healthcare, a unit of UnitedHealth Group that manages the nation’s largest health care payment system. The assault shut down Change’s digital billing and payment routes, leaving hospitals, doctors and pharmacists without ways to communicate with health insurers for weeks. Patients were unable to fill prescriptions, and providers could not get paid for care.

While some earlier cyberattacks affected a single hospital or smaller medical networks, the breakdown at Change, which handles a third of all U.S. patient records, underscored the dangers of consolidation when one entity becomes so essential to the nation’s health system.

Ascension systems remain down indefinitely, but doctors and nurses are working to find ways of getting access to some information about patients’ medical histories by looking at health records kept by other providers. Ascension is also telling doctors and nurses that they will soon be able to see existing digital records.

“It is a huge disruption for everyone involved,” said Kristine Kittelson, a nurse with Ascension Seton Medical Center in Austin, Texas, who is a member of the National Nurses United union.

The Ascension attack has had a similarly widespread impact as Change, with some hospitals in Indiana, Michigan and elsewhere diverting ambulances. Ascension hospitals handle roughly three million emergency room visits a year and perform nearly 600,000 surgeries.

Like Change, Ascension was the subject of a ransomware attack, and the hospital group says it is working with federal law enforcement agencies. The attack appears to be the work of a group known as Black Basta, which may be linked to Russian-speaking cybercriminals, according to news reports.

There are concerns that the hackers could release private medical information, and patients have already begun filing federal lawsuits against Ascension saying it did not do enough to safeguard their data.

Large health care organizations have increasingly become a prime target for cybercriminals, intent on creating as much havoc as they can on a vital part of the U.S. infrastructure. “This is something that is going to happen over and over again,” said Steve Cagle, the chief executive of Clearwater, a health care compliance firm.

With a sprawling network of hospitals and clinics, big organizations have not yet identified where they are vulnerable and how to minimize the disruption of a serious attack. The industry “never planned for this,” Mr. Cagle said.

While Ascension continues to treat patients, the dangers of missing pieces of a patient’s history are palpable. In interviews, doctors and nurses outlined the threats to patient care: People may not remember what medications they are taking; previous visits may be omitted as well as the outcome of earlier procedures or tests.

In Austin, Ms. Kittelson said she had to search through dozens of pieces of paper to find what medication a doctor may have ordered or to find something about the patient’s status. “I’m worried about the charting,” she said, noting that she had been painstakingly chronicling a patient’s condition and treatment by hand.

And many of the routine safeguards have not been available. Nurses couldn’t scan a medicine and a patient’s wristband to make sure the right patient was getting the right drug, increasing the odds of a medication error. And they have grown far less certain that doctors have received important updates of a patient’s status.

“Our big issue is that the cyberattack has crippled the nurses,” said Lisa Watson, a union nurse at an Ascension hospital in Wichita, Kan. She noted that the workload had significantly increased.

“This is much more than the old-time paper charting,” Ms. Watson said. Nurses have had to write prescriptions and other treatments on separate forms that go to different departments. Instead of getting immediate alerts on a computer, a nurse may not see a new lab result for hours.

On Tuesday, Ascension said it was “making progress in both restoring operations and reconnecting our partners into the network,” and some nurses say they may soon have limited access to previous records. But Ascension has not offered a timeline for restoration of full digital access, saying in an emailed statement Tuesday night only that “it will take time to return to normal operations.”

Few providers were willing to publicly discuss the extent of the damage wrought by the ransomware attacks, across many states and medical departments. The havoc has yet to be fully assessed, and Ascension is intent on keeping as much of its operations open as possible.

Union nurses say the cyberattack has worsened staffing shortages. The issue has dogged labor relations with Ascension, although the company has denied it. Nurses in Wichita recently clashed with the hospital’s management over whether there were too few nurses in the intensive care unit.

“Despite the challenges posed by the recent ransomware attack, patient safety continues to be our utmost priority,” Ascension said in an emailed statement. “Our dedicated doctors, nurses and care teams are demonstrating incredible thoughtfulness and resilience as we utilize manual and paper-based systems during the ongoing disruption to normal systems.”

“Our care teams are well versed on dynamic situations and are appropriately trained to maintain high-quality care during downtime,” it added. “Our leadership, physicians, care teams and associates are working to ensure patient care continues with minimal to no interruption.”

Ascension said it would tell patients if an appointment or a procedure might need to be rescheduled. The organization has not yet determined whether sensitive patient data has been compromised, and it is referring the public to its website for updates.

The risks to patient care from cyberattacks have been well-documented. Studies have shown that hospital mortality rises after an attack, and the effects may be felt even by neighboring hospitals, lowering the quality of care at the hospitals forced to take on additional patients.

An added concern is whether sensitive patient information has been compromised and who should be held accountable. In the fallout from the Change attack, doctors are pushing U.S. government health officials to make clear that Change bears responsibility for alerting patients. According to a letter from the American Medical Association and other physician groups earlier this week, doctors urged officials to “publicly state that its breach investigation and immediate efforts at remediation will be focused on Change Healthcare, and not the providers affected by Change Healthcare’s breach.”

These kinds of ransomware attacks have become increasingly common, as cybercriminals, often backed by criminals with ties to foreign states like Russia or China, have determined just how lucrative and disruptive targeting large health organizations can be. UnitedHealth’s chief executive, Andrew Witty, recently told Congress the company paid $22 million in ransom to cybercriminals.

The Change attack has drawn a lot more government attention to the problem. The White House and federal agencies have held several meetings with industry officials, and Congress asked Mr. Witty to appear earlier this month to discuss the hack in detail. Many lawmakers pointed to the increasing size of health care organizations as a reason the nation’s delivery of medical care to millions of Americans has become more increasingly vulnerable.

Experts in cybersecurity say hospitals have little choice but to shut their systems down if a hacker manages to gain entry. Because the criminals infiltrate the entire computer system, “hospitals have no choice but to go to paper,” said Errol Weiss, chief security officer for the Health Information Sharing and Analysis Center, which he described as a virtual neighborhood watch for the industry.

He says it would be unrealistic to expect a hospital to have a backup system in the event of a ransomware or malware attack. “It’s just not possible and feasible in this economic environment,” Mr. Weiss said.