[ad_1]

Gov. Gavin Newsom should have learned this four years ago: You don’t try to sell voters on more government spending in a primary election.

Particularly Sacramento spending.

Newsom’s Proposition 1— a proposal to pump more money into treating homeless people who are mentally ill, drug addicted or alcoholics — may finally pass after vote counting is completed. But as of this writing, it is still too close to call, with the yes and no votes virtually even.

Newsom must be shocked.

In January, the cocksure governor told Times reporter Taryn Luna in an interview: “I think it’s going to win overwhelmingly. Period. Full stop.”

Typical Newsom hubris.

Many politicos were surprised last year when he insisted that his proposal be placed on the March 5 presidential primary ballot. Primary elections are often graveyards for liberal causes.

That’s because they typically suffer from low voter turnouts. And that helps conservative agendas. When turnouts are low, the electorate consists of a higher proportion than usual of right-leaning voters, including older white people and Republicans.

In this election, the final turnout will probably be a pathetic 33% of registered voters, says Paul Mitchell, who runs Political Data Inc.

So far in the vote count, 38% of Republicans have returned their mailed ballots, compared with only 31% of Democrats, Mitchell says. Also, 51% of voters over age 65 have sent back their ballots, compared with just 13% of those under 35.

White people account for 67% of those who cast ballots, although they’re only 55% of registered voters. Conversely, Latino voters make up just 17% of the ballots cast, although they amount to 28% of those registered.

“When the youth turnout drops, Latino turnout drops with it. Latinos are younger,” Mitchell says.

Four years ago in a March 3 presidential primary, the turnout was a bit higher: 47%. But it wasn’t pro-Democrat enough to rescue a $15-billion school construction bond proposal that was crafted in the Legislature with Newsom’s heavy input and support. Voters rejected it by six percentage points.

The proposition number — 13 — may have confused voters. The measure’s backers theorized that people feared it would weaken the sacrosanct 1978 property tax reduction initiative, Proposition 13. Maybe some did. But the real reason it failed was that the turnout was low and voters objected to the spending.

That measure should have been placed on the November general election ballot when the turnout was 76%.

In 2008, on an even earlier presidential primary ballot — Feb. 5 — voters rejected a measure to spend more money on community colleges.

You’d think Newsom would have understood the lesson.

“Always go to the general election if you’re going to ask voters for money,” says Democratic consultant David Townsend, who has run many local bond and tax measures.

“There are more liberal voters and they’re younger. They have a longer view of life. They want things to be better for themselves. Primaries have a bunch of old guys like you and me.”

Across California on March 5, roughly as many local school bond measures failed (14) as passed (15), according to the California Taxpayers Assn. Some measures are still too close to call.

Newsom’s Proposition 1 included a $6.4-billion bond. But the cost would double when interest on the borrowing is added. Not all voters are dumb. Many do the math — and frown about the many billions California already has spent trying to reduce homelessness.

The Proposition 1 money would finance construction of 4,350 housing units. There’d be new treatment facilities for 6,800 homeless people. Newsom hyped the housing number higher.

Perhaps if the governor had focused more on selling his confusing ballot measure and less on promoting his national political profile, Proposition 1 would have fared better. But mainly, the proposal did worse than expected because it was placed on the wrong ballot — despite Newsom raising more than $20 million for the campaign and opponents spending virtually zilch.

Good day for moderate Democrats

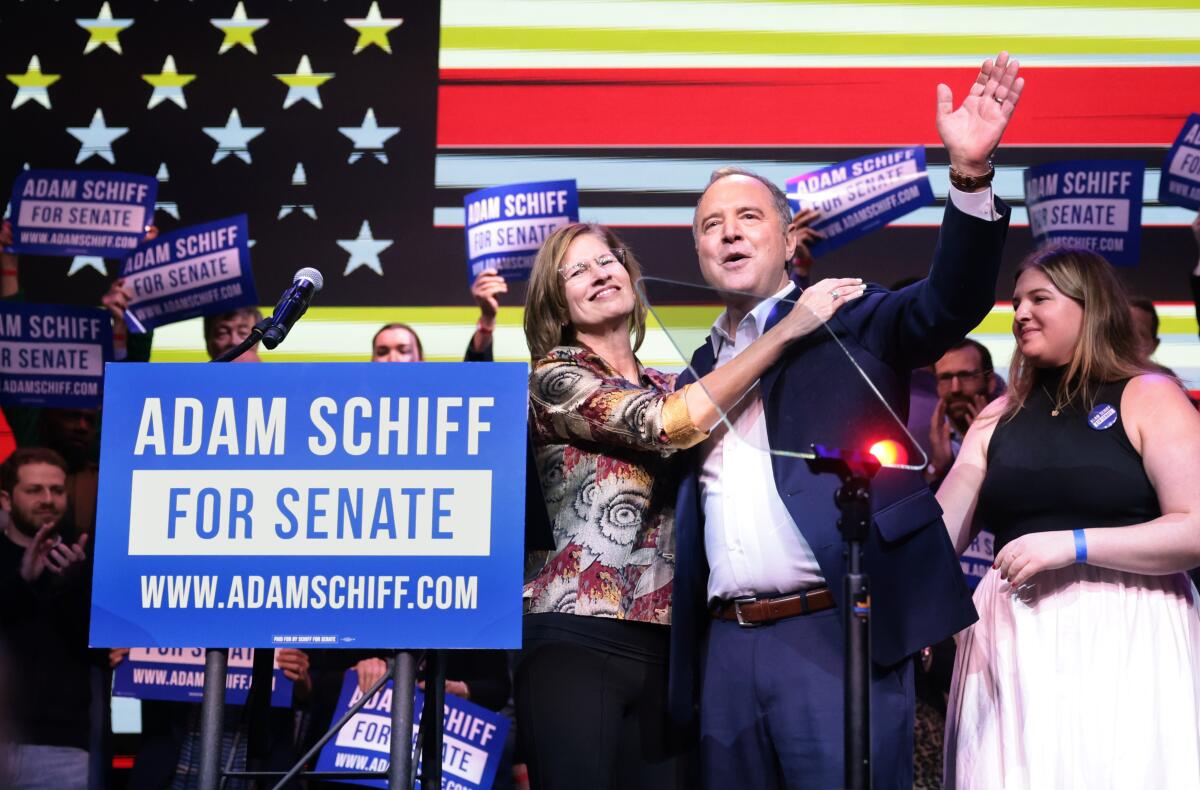

Rep. Adam Schiff (D-Burbank) celebrates with his wife during an election night party in Los Angeles as he seeks to replace Sen. Dianne Feinstein in the U.S. Senate.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

It was a bad day for several Sacramento politicians, especially liberals. It’s looking like at least 10 legislators seeking another office failed.

Several moderate legislative candidates did well. But the next Legislature elected in November will still be dominated by liberals.

“By and large, it was a pretty good night for the moderate side,” says Marty Wilson, chief political strategist for the state Chamber of Commerce. “It was a solid performance by business-backed Democrats.”

In the U.S. Senate race, the more moderate candidate — Democratic Rep. Adam B. Schiff of Burbank — easily beat out two more liberal Democrats, Rep. Katie Porter of Irvine and Barbara Lee of Oakland.

But I suspect Schiff’s victory was due mainly to his solid name identification earned by being the House’s leading anti-Trump crusader.

Likewise, Republican Steve Garvey finished in the top two — qualifying for the November ballot — because of fame gained by being a former star ballplayer for the Los Angeles Dodgers and San Diego Padres.

Schiff’s cynical TV ads boosting Garvey among Republican voters to assure that Porter didn’t become his November competitor probably weren’t needed at all. He could have emerged with a cleaner image.

Porter ran a poor campaign, emphasizing issues that didn’t click with a low-turnout electorate, railing against corporate corruption of politics. Unmoved voters probably asked: Yeah, what else is new?

Lee was the most impressive candidate for me. She handled herself well and stuck to her principles, even if they were far too liberal, even for California. No one will get elected senator advocating a $50 national minimum wage.

All that said, there must be a way to count votes faster — even while painstakingly making sure they’re legit.