[ad_1]

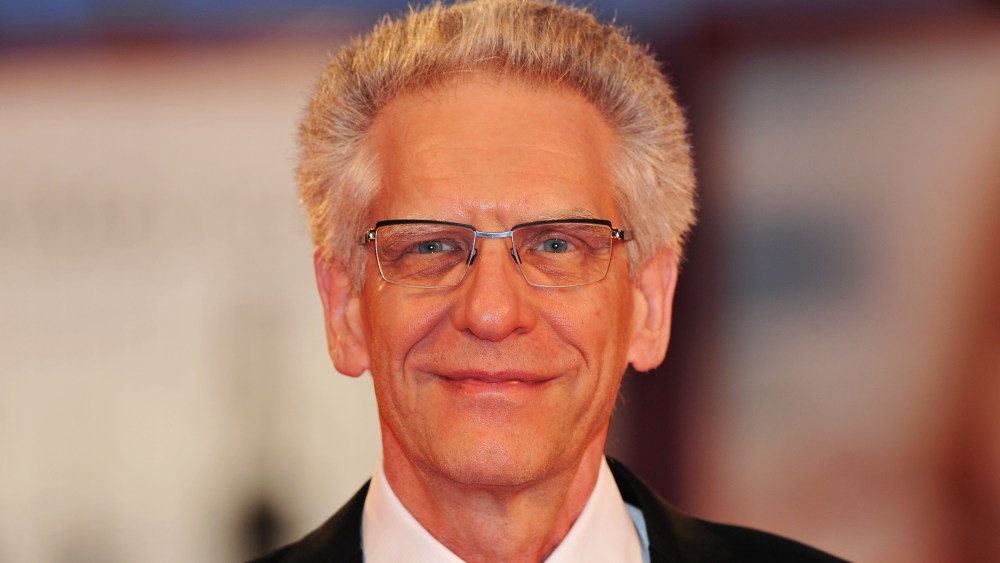

David Cronenberg is returning to Cannes with “The Shrouds,” the story of an industrialist named Karsh, who invents a controversial technology that allows grieving families to see inside the graves of their loved ones with high-resolution cameras.

It’s a film that defies easy categorization. This being a Cronenberg production, there are elements of body horror, but there’s also a conspiracist undercurrent, as Karsh (Vincent Cassel) begins to suspect that shadowy forces are undercutting his expansion plans after his cemetery is ransacked. He has his own reasons for developing his business. Karsh’s wife died after a brutal fight with cancer, leaving him inconsolable. He begins to question if her death may be part of a larger plot by the medical establishment.

The material has personal resonance for Cronenberg as well. His wife, Carolyn Cronenberg, died from cancer at the age of 66, and the unyielding grief that he felt over her loss led him to make “The Shrouds.”

“The Shrouds” has been described as a personal film. In what ways is it personal?

It was partly inspired by the death of my wife in 2017. We had been together for 43 years. Really all my movies are personal in some way or another, even a movie like [the Carl Jung-Sigmund Freud drama] “A Dangerous Method,” for example, which wouldn’t seem very obvious. It’s not necessary for the audience to know all that. It’s not really relevant to the film experience, in my opinion. And I feel the same about “The Shrouds.” That is to say, the fact that it might have personal meaning to me and that there might be some lines of dialogue that came from my actual experience of life doesn’t therefore make it a good movie. The movie has to stand on its own.

When did you come up with the idea for “The Shrouds”?

It was pre-pandemic. I went to L.A. to pitch it to Netflix. At that point it was a well-formed idea, but it wasn’t a script yet. The people I talked to there were very receptive, and Netflix gave me the OK to start writing what they call the prototype, which was the first episode of what was then going to be a series. And then they liked that enough to tell me to go ahead and write the second episode. After that they decided not to go forward for various reasons.

Did Netflix tell you why they ultimately passed on it as a series?

Yes, they gave me a classic reason. They said, “It wasn’t what we fell in love with in the room,” which to me was a very Hollywood thing to say. I had been hoping that Netflix was not as Hollywood as Hollywood. I was baffled because I thought I was very specific with them, but I guess we disagreed on where we thought the series should go. What can you do?

What they fell in love with in some way was me, which is flattering. They asked me in the room that day, where did this idea come from, and I said: “How dark do you want to go?” I guess they thought it was going to be a very intimate and personal grief movie. I never saw it as being just that — it’s a huge element of it, of course. But it wouldn’t have interested me if that was the only thing it’s about.

How different is the feature film from the Netflix series you envisioned?

The movie ends with the protagonist on a plane heading to Hungary. Episode 2 would have picked up with his arrival there, and then the idea was that he would go to one location after another as he tries to expand his cemetery business into an international franchise. And he would get involved in the politics of different countries and see the different ways they treated graves — burying the dead is hugely significant in just about every culture, but customs vary dramatically. I wouldn’t say the film ties things up neatly, because it’s still very open-ended. But it does go further in terms of developing a sense of where these characters are in the future.

Was making this movie part of your grieving process?

I don’t really think of art as therapy. I don’t think it works that way. If you’re an artist, everything you make, you work out of your life experience, no matter what that is. Whether you’re rehashing something from your distant past or your present circumstances, there’s always creative energy that can be mined from your life. But grief is forever, as far as I’m concerned. It doesn’t go away. You can have some distance from it, but I didn’t experience any catharsis making the movie.

In “The Shrouds,” Diane Kruger plays the twin sister of Vincent Cassel’s late wife, Becca. The two grow closer and begin to suspect that Becca may have been a victim of a medical conspiracy. Why do conspiracies interest you?

I wanted to play with the idea of paranoia. Conspiracies can be a grief strategy. If you’re an existentialist like me or an atheist like me and like Vincent’s character, you don’t have religion to fall back on. You can’t say, “I might get to see my dead wife again in heaven.” You may come to the point where you think, there is no meaning to the death of this person. And that is really quite unbearable. The fact that it’s meaningless. And so, to find meaning, which we have evolved to seek, it is somehow comforting to think that there was a conspiracy, and that this person was part of a plan — that this person has been murdered or that it was all part of a medical experiment gone wrong.

There is something irresistible about conspiracies. They have this kind of propulsive momentum. In your film, they are so attractive that Diane Kruger’s character gets turned on sexually by them.

What makes them so alluring is the access to power that you feel. You think that you have this knowledge that other people don’t. And that gives you power, and it makes you a kind of detective or secret agent who knows something about how the world works behind the scenes that no one else sees. That energizes you, and it’s exciting. And that can even become sexually charged in certain circumstances. At least, that was my take on it.

In the film, Vincent Cassel looks a lot like you — at least his hair looks like yours. Was that a conscious decision on your part or his?

I didn’t cast Vincent because of his hair. Let’s just say it was a lucky accident. But Vincent’s approach as an actor was this character is David, and I am going to try to replicate David. He’s wearing clothes that I would not normally wear, and his hair is coiffed a little more carefully than mine. But undeniably he’s done a very good job of looking and sounding like me. I did tell him that I would like him to try to replicate my accent, because the movie does take place in Toronto and my accent is basically a midtown Toronto accent. Actors need to access the history of the characters that they play, so Vincent used me as a template.

Was it all strange to direct somebody who looked like you acting out scenes that you had written about something so personal?

It was totally normal. [Chuckles] No, but it wasn’t unusual, because as a writer and director, you are each character. When you are sitting on your computer writing, you’re embodying that character. And so, it’s normal that all of the characters are really me in some way. But when you’re directing, you must have a certain distance, calmness and tranquillity to see things clearly. The emotion is underneath you as you’re directing. But it is quite far underneath. And you’re mainly now working as a craftsman. It becomes about the demands of the craft — the lighting, the camera movement, controlling all those things.

You said something that I found very moving. And I’m paraphrasing, but it was basically that despite not being religious, you have a conviction that people do live on beyond just our memories of them, through the DNA that we share with family members. Is that comforting?

On a day-to-day, mundane, living-our-lives existence, none of that helps. That your children carry your dead wife’s DNA, as well as yours, is not really a comfort when you don’t have that wife that you lived with intimately for 43 years. But just moving one step away from that, it is an undeniable physical reality. And for me physical reality is the most real you can get. There’s philosophical reality and a political reality, but body reality is the real reality. So in terms of DNA, this is a modern version of what has been known for thousands of years — that your children are a continuation of you, and you are a continuation of your parents, for good or bad. It’s definitely there, and you can feel it. I can feel it physically.

What do you mean you can feel it physically? You see a parent’s imprint in gestures or expressions that you make?

I can suddenly become my father. I make a movement that he would have or react in a certain way. I have a nephew who really reminds me of my father. These things are physically accessible if you are attuned to them. This is not spiritualism; it’s not religion. To me, it’s very physical, downstairs, real stuff.

So many of us pass through life and we touch people and leave a mark, but it’s ephemeral. Most of your family are artists or filmmakers — your wife was an editor; your children are directors and writers. You all leave something tangible behind in the movies you make. Is that part of the attraction to making art?

Only in retrospect. There were so many incredibly popular artists in the past who have disappeared without a trace beneath the waves. They’re gone. So it’s not something that you can depend on or rely on. You don’t know what the fate of your work might be. Of course, once you’re dead it’s totally irrelevant. Which either makes you sad and depressed or makes you rather happy. It means, hey, don’t worry if it doesn’t work out. Once you’re dead, it doesn’t matter.

In the film the technology that Vincent’s character creates — cameras that allow families to see inside the graves of their spouses or relatives — feels very cinematic. Was that intentional?

Oh yes. Vincent’s character, Karsh, was a maker of industrial films before he did this. So he is concerned with the clarity of the image and the technology of the cameras. He calls it “Shroud cam” and he uses them as an all-enveloping 3D camera. It’s a strange cinematic technology that involves corpses and gravestones. And he’s very proud of his latest 8K version, which gives users incredible resolution, and he talks about how the technology allows you to rotate the image of your decomposing loved one and zoom in on things.

Why is that appealing? I’ve lost loved ones. I don’t think I would want to see their corpses decompose on-screen.

As Vincent says: “When they lowered my wife into the ground, I wanted to be in the box with her.” And I had that same feeling. I didn’t want to be dead. But I had a desire to be there with the future of a body that had meant so much to me over the years. In this film, I have invented a clientele for the cemetery that probably doesn’t exist. Most people would react the way you react. It might be completely unrealistic.

I also want to ask you about bodies themselves. I think about bodies externally. How they present to us at first glance — people’s skin, their eyes, their hair. In your movies, you often show what’s underneath. Their bones, their organs, their sinew, their musculature. Is that how you see people?

Are you going to Cannes? Because when I look at you, I’ll let you know what I see. Of course, it begins with the eye. As Yeats wrote, “Love comes in at the eye.” It’s that first visual representation of somebody that attracts you or not. But then, eventually, when you get to know someone in, let’s say, a romantic relationship, discussion of the body usually follows — you know, aches and pains, medical things. It used to be cliché that when old people get together all they talk about is their medical conditions. But I notice with my children and grandchildren that it happens very early now. You have very young people talking about all this stuff, and a lot of them are getting implants and various touch-ups done to them. It’s not just me who is thinking about what is going on inside the body. Everybody is more aware of their bodies and not just in an exterior sense.

You took an extended break from filmmaking — you premiered “Maps to the Stars” in 2014 and then didn’t make another movie until 2022’s “Crimes of the Future.” Now, you’ve come out with two films in rapid succession. Are there other movies that you’re hoping to make?

I have no idea what’s next for me. Part of those years were taken up with taking care of my wife as she underwent chemo. When I reemerged with “Crimes of the Future,” I wanted to see if I would have the stamina to do this. It takes a lot of energy and endurance to make a movie, and you wonder if you still have it. I found that it felt just the same.

But another issue, speaking of bodies, is getting insurance. There are pragmatic concerns. If you can’t get insurance, will the producers take a chance on you? It’s a big issue for aging filmmakers, and I am certainly among them.