[ad_1]

The world’s oldest known library, the Royal Library of Ashurbanipal, in what is today Iraq, was created in the seventh century B.C.E. to store clay tablets used for recordkeeping. Its librarians preserved 30,000 of them—including the 4,000-year-old Epic of Gilgamesh. And Egypt’s Great Library of Alexandria acquired an enormous collection: In the third century B.C.E., the law required travelers arriving at the city’s bustling seaport to hand over any books in their possession to library scribes, who would return a copy of the book to the owner and keep the originals. Such texts helped make the library a beacon of knowledge and learning in the ancient world.

Today the U.S. Library of Congress continues the tradition of conserving knowledge with one of the largest library collections ever compiled. It is home to more than 175 million works humans have produced, from e-books to ancient scrolls, which it aims to preserve for future generations.

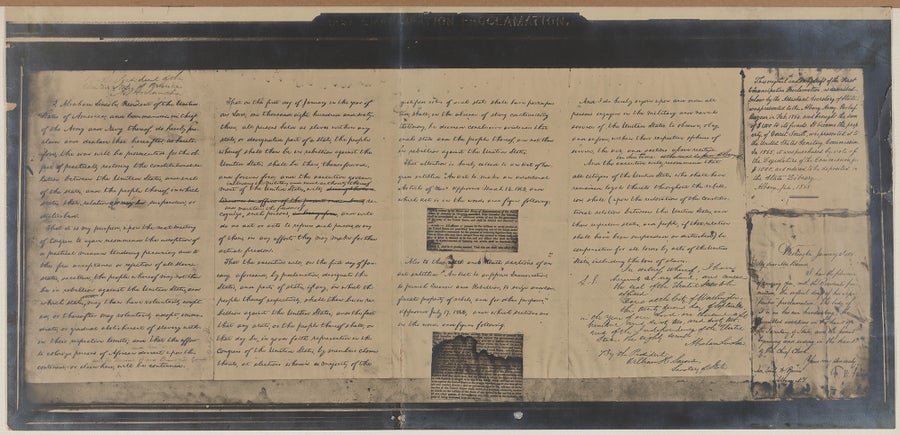

The library’s role as the research arm of the U.S. Congress and a preserver of primary sources in American history means it has some of the U.S.’s most important documents, including a rough draft of the Declaration of Independence and Abraham Lincoln’s first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation. But its scope extends far beyond the country’s borders; items such as 2,000-year-old Mesopotamian clay tablets and 18th-century Iranian prayer scrolls (written on parchment made from gazelle skins) are among its artifacts—along with Atari video games. Approximately half its collection is not in English.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Produced in Iran in the 18th or 19th century, this small scroll is written on nearly transparent parchment made from the skin of gazelles. It is called a hijab scroll, in the sense that it veils its meaning and offers protection from evil through sacred text.

Along with physical media, as of 2024, the library held about 184 petabytes of digital information, from three-dimensional digitized artifacts to patents. Converted into DVDs, that would be about 39 million disks. And if those disks were stacked atop one another, they would tower 29 miles high—a span equivalent to about 106 Empire State Buildings.

Selection by the Library of Congress is meant to ensure an item will be available for researchers hundreds of years from now. But even a library this extensive can only preserve a fraction of the books published annually around the world, not to mention the scholarly articles, legal materials, international reports, newspapers, songs, television series and video games.

To learn more about how the Library of Congress makes its weighty decisions about shaping our society’s collective memory, Scientific American spoke with the library’s collection development officer Joseph Puccio, who retired last month, and director for preservation Jacob Nadal.

An Atari video game console and joystick, one of many iconic toys thru the decades for the parenting special section, on August, 23, 2017, in Washington, D.C.

Bill O’Leary/The Washington Post via Getty Images

[An edited transcript of the interview follows.]

When people think of libraries, they think of books. Can you tell us more about the wide range of things you collect for the Library of Congress?

NADAL: We have every format people have ever used to record their knowledge and creativity: books, obviously, manuscripts, maps and even cuneiform tablets, which are probably the oldest thing we work with. We have the earliest motion picture films, which are yards of rolls of prints of every frame of the film, as well as [glass-based lacquer disks and] digital music and video games.

PUCCIO: Our fundamental collecting policy is the Canons of Selection, issued in 1940. There are three principles: The first is that we should have everything that Congress needs to do its work. The second is that we should possess the materials that cover the life and achievement of the United States. And the third is that we’re not in a vacuum, and we need stuff from the rest of the world. We are constantly taking snapshots of the world. We’re always concerned when, for budgetary reasons, we might not be able to collect in a particular area of the world—because sometimes you cannot go back and fill in those gaps. Maybe, with digital, it will be different in the future. But right now, if you miss picking up materials, you may not get a copy five years later.

Where do the materials you consider for preservation come from?

PUCCIO: We have various acquisition streams, such as copyright deposits (the library houses and oversees the U.S. Copyright Office). We have selection officers and other staff who apply our collection policies when looking at the flow of material. We also receive a lot of gift materials. Sometimes we will go out and try to convince someone to give us their collection of manuscripts or photographs. Then we have the purchase acquisition stream. Each year Congress appropriates money for the library to acquire materials, and we use most of that to acquire electronic resources and materials from outside the U.S. We give book dealers in other countries descriptions of the types of books we want, such as prizewinners. We also have six field offices of the library—in Cairo, Egypt, Islamabad, Pakistan, New Delhi, India, Jakarta, Indonesia, and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

How do you choose what to keep?

PUCCIO: When we acquire something at the Library of Congress, it’s with the idea that we’re keeping it for forever. We try to encapsulate our hopes for how we build the collection through 75 or so policy statements, which are mostly by subject. They range from law through to children’s literature to LGBTQIA+ studies. We then have collecting levels from zero through five. Five says we want to be really, really strong in that subject; three says we want enough content so that we can answer questions on this subject from Congress. At zero, we do not collect at all.

An original draft of the first Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Abraham Lincoln.

As part of the library’s general assessment program, which looks for gaps in the collections, we found that there were a number of countries, such as Morocco, for which we have received no children’s books for several decades. The children’s literature Collections Policy Statement indicates that we aim to collect these types of books from outside the U.S. at a level three—approximately midrange between out of scope (zero) and comprehensive (five). Our collecting has been very Eurocentric, and in the next phase of this program, we will work toward filling the gaps where possible.

We have about 200 recommending officers in the library who are responsible for different subject areas. They know what researchers need now, and hopefully they can see the future to try and understand what a researcher in 100 years will need.

But with the volume of materials, they don’t have the time to take a really close look at each item. Comprehensive collecting is impossible—especially when you look at the fact that there’s like a billion websites out there. That’s why we refer to the policy statements and the zero-to-five collecting levels.

How much space do you have to store all this material?

NADAL: There are three buildings on Capitol Hill: the [Thomas] Jefferson Building, with a capacity of seven million items; the [John] Adams Building, which has a giant block of books in the middle of about 12 million volumes; and the [James] Madison [Memorial] Building, [which] has a number of our special format units, such as manuscripts, maps, prints and photographs and music. We also have a facility at Fort Meade in Maryland, with roughly 100 acres, where we’re planning for our eighth building, and the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center down in Culpeper, Va.

PUCCIO: We don’t have enough space. We never have, not since 1870, when the Copyright Office became part of the Library of Congress. Back then there were books all over the place—you can see it in the pictures—and we still have books on the floor here on Capitol Hill. On the digital side, it’s easier to buy digital storage than to build a warehouse. The major challenge is that we never have enough money to acquire everything we want. When we acquire an item, that means preserving it and finding storage for it. So, it’s not just the act of paying $75 for a book. It’s thinking about how much that’s going to cost over 100 years.

If the building was burning, what would you run out with?

NADAL: I would do nothing. We have two Preservation Emergency Response Teams that are on call 24/7. And when it comes to digital, we have the three-two-one rule: three copies in two different formats in one other geographic region. We put a great deal of effort into thinking through what materials we do have. If they were lost or damaged in some way, it would harm the human record. There are many layers of protection around those materials to put them beyond the reach of accident.

We always sort of jokingly say that we have no favorite collections, except whatever is on a conservator’s bench right at the moment. Our curation and interpretation of objects can change as we learn more about them, so preservation often becomes a different window into understanding the objects in our collection. For example, we have Ethiopic prayer scrolls: They’re charms or talismans to protect the wearer and were often the same height as the person using it. And so we have a record of the heights of people from a different time and place. That’s really, I think, where the science and the conservation can become really exciting around here.