[ad_1]

Norman Mailer is the kind of writer people now tend to look at and appraise by saying, “He could never get away with that today.” And maybe that’s true. In Mailer’s case, however, the that they’re referring to could be any of the following things: his confrontational public statements; his misbehavior on talk shows; his ardent bad-boy meditations on subjects like sexuality and violence; his propensity to drink and drug and fight (he liked to literally butt heads with people at parties); and great lyrical swaths of his writing.

Forget what Mailer could or could not get away with today. He was feeding the fire of controversy and provocation 50 and 60 years ago; even then, he was considered a figure of singular outrage. Yet it was all part of his mission to make a difference in his time, to wake us all up — to what was happening in society (not just the busy surface but beneath it), to how the government and the corporation were working in cahoots to perfect a new brand of authoritarianism (something he was explicitly onto in — yes — 1948), to the secrets and mysteries we were living inside. When Diana Trilling, the venerable lioness of a literary critic, declared Mailer to be “the most important writer of our time,” she wasn’t kidding around.

Nobody wrote sentences like Norman Mailer. Sentences and thoughts like this one, which you hear him speak in the haunting documentary “How to Come Alive with Norman Mailer“: “A sense of light diminishes in all of us, which I think is the modern disease — that we’re all becoming duller, more conventional, more unimaginative. Technology drives us further and further away from our instincts. We’re flattening out people’s spirits. We’re surrounded by faces, but everyone is always incredibly alone.” For Mailer, a passage like that is really a kind of gauntlet, an exhortation to all of us to turn away from the machine and plug back into something elemental.

That’s one of the things he stood for; it’s what made some of us cleave to his writing like a totem. Yet Mailer was also a fully fledged media character, confessionally sincere yet self-created (the way he might have put it is: His public identity was a product of his own imagination and too much feedback). And part of the lure of “How to Come Alive with Norman Mailer” is that though it’s a reasonably straightforward biographical portrait, in 100 minutes it weaves together multiple levels and dimensions of The Mailer Experience. It’s about Mailer the writer, the celebrity, the failure, the intoxicated underworld-of-the-’50s searcher, the culture warrior and provocateur, the literary comingler of fiction and reality, the filmmaker, the serial husband and paterfamilias, the talk-show firebrand, the self-dramatizing hoodlum who stabbed his wife…AND the obsessive artist.

The film opens, almost like a thriller, with the stabbing, which is Mailer’s most infamous episode and the one that, in a sense, he spent the rest of his life living down. He becomes, from the start, almost the villain of his own story. The incident happened in the wee film-noir hours of a party in 1960. His marriage to Adele Morales had become increasingly fractious, the two of them going at each other, and when she mocked him at that party, he came at her with a pen knife; she could have died. You could make an entire documentary about this event, and for many people, especially today, it stands as a deal-breaker. They would not be interested in lending attention or credibility to a man who’d do such a thing.

But one need not waffle about this moment of Mailer’s descent into an all-too-human evil. The film makes no attempt to rationalize or defend it; neither does Mailer. But the film insists, at the same time, on the complicated majesty of his writing — and on how, in this case, Mailer’s attempt to reckon with what he’d done fed into his transformative 1965 novel “An American Dream,” which was like “Crime and Punishment” reset in the world of New York glitz and power. That novel understands, as does the film, that Mailer’s darkest moment was a looking glass he passed through.

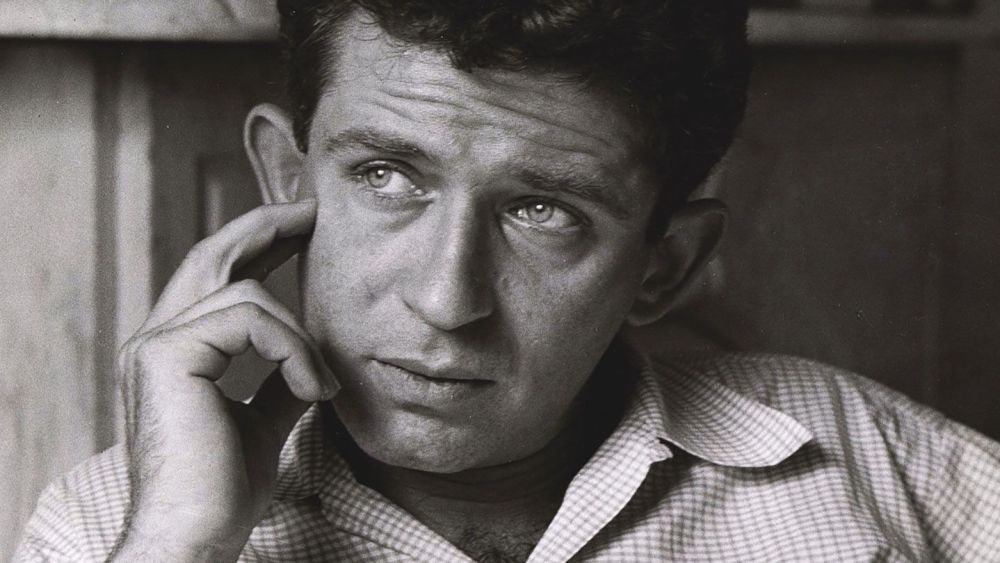

The director, Jeff Zimbalist (who also made the great scaling-skyscrapers documentary Skywalkers: A Love Story, which drops on Netflix this Friday), looks at Mailer with a supreme fusion of understanding and critical wisdom. The archival footage that Zimbalist has assembled with extraordinary dexterity allows us to revel in the shaggy angry sexy furrowed-brow charisma of the Mailer persona. He had a gift for turning every encounter into a kind of mind game. (The one time I met him, at a party for his 1987 movie “Tough Guys Don’t Dance,” which I had panned, he looked right at me, as he was holding a drink in each hand, and said, “Just because you think you’re in my head doesn’t mean I’m not in yours.”)

But the film is also an acute psychological portrait that traces the journey of how Mailer evolved, which it presents as his “rules for coming alive,” starting with “Don’t Be a Nice Jewish Boy,” extending through “Be More Wrong Than You’re Right” and “Be Willing to Die for an Idea.” “Be More Wrong Than You’re Right” is one of the keys to Mailer. He was willing to wander out onto the limb of his ideas, to push what he thought until he was flying on intuition more than Apollonian rationality. That’s why he wasn’t always “right.” And it’s also why his writing could leave you stoned; he’d penetrated beyond the surface and touched the inner hum of what was real.

Mailer was married six times and had nine children, six of whom are interviewed in the documentary. He was an absentee father (to put it mildly), gathering his kids together for summers in the Hamptons, yet they all seem to adore him. He had a bearish protective quality. The film also dives into the jaw-dropping places that his impulse toward performance-art media exhibitionism led him to. The first is his self-directed movie “Maidstone” (1970), a heightened vérité ramble that the film rightly suggests was the unconscious birth of reality TV; it climaxed with Rip Torn deciding that the film needed to end by “killing the king,” so he attacked Mailer with a hammer on camera (Mailer responded by biting through Torn’s ear), all of which we see, and all of which makes you realize why the 1960s needed to end.

The other vérité revelation is the face-off between Mailer and four prominent female thinkers — Germaine Greer, Jacqueline Ceballos, Jill Johnston, and the aforementioned Diana Trilling — that took place on April, 30, 1971, at New York’s Town Hall, all pegged to the release of “The Prisoner of Sex,” Mailer’s searching meditation on men and women and sexuality in the age of feminism. It was captured in the D.A. Pennebaker film “Town Bloody Hall,” which we see extensive clips of here. You’d think, surveying the setup, that Mailer was the male-chauvinist enemy, but the richness of this night is that he had a profoundly engaged response to the rise of women, and these feminist firebrands, notably Germaine Greer, had a grudging affection for him. It’s easy to dump on Mailer as the intellectual Defender of Macho, but the truth is that he was igniting passionate exploratory battles that are still going on.

Too often these days, documentaries about artists lack incisive critical voices. “How to Come Alive with Norman Mailer” has a number of them, from the trenchant James Wolcott to the magisterial Mailer biographer J. Michael Lennon to the wry Daphne Merkin to the timelessly brilliant David Denby, who evokes the spiritual engine of Mailer’s writing with extraordinary intimacy. “How to Come Alive with Norman Mailer” holds surprises even for Mailer fans. Yet as much as Mailer, with his braggadocio and heady male swagger, may not seem like he fits snugly into this day and age, I strongly suspect that if you’re a young person who’s a reader and you’ve never read a word that Norman Mailer wrote and you saw this movie, you’d be looking up one of his volumes within a day. And if you started to read it, you’d have the sensation that so many of us have had. You’d be hooked.