[ad_1]

In the last decade, the Maltese film industry has undergone radical development, with a strong focus on seeing the island country evolve from a service provider to Hollywood productions to telling their own stories on screen.

Speaking with Variety ahead of the second edition of the Mediterrane Film Festival, Maltese filmmakers have highlighted the importance of fostering local talent, rerouting foreign investment into native productions and strengthening bonds with neighboring countries in the Middle East and North Africa.

“Things have changed drastically in recent years,” said veteran filmmaker Mario Philip Azzopardi, whose 1971 “Il-Gaġġa” is widely presumed to be the first full-length feature filmed entirely in Maltese. “The building of shooting facilities, especially the water tanks, attracted a lot of movies and now there’s the attraction of 40% tax rebate. The problem is we have become primarily a service country, and creating Maltese movies is extremely difficult. We can’t afford the budgets of foreign films.”

The Canadian-Maltese filmmaker, who spent most of his career in Canada but recently returned to live in his home country, emphasized the importance of the co-production model. “You see great movies coming out of countries like Turkey and Spain, but they have the market for it. We don’t have the market yet. We must work in a co-production model like I have done with Canada. This is how we survive.”

Alas, this model also presents its challenges, the biggest being the disparity of representation between co-producing countries. “When you work in co-production, the leads are never really Maltese. These are sales requirements, companies need big names to draw investment. Crew-wise, it is fantastic. We had a 99% Maltese crew on Canadian co-productions.”

The sentiment is echoed by Alex Camilleri, whose feature debut “Luzzu” premiered to great acclaim at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival. “We’ve got incredibly talented and inspiring local crews in all departments. Some of the best people in the world work here. They get trained on big productions, but those productions rarely provide an opportunity to graduate to head of department.”

Much like Azzopardi, Camilleri recently relocated to Malta from North America after living and working in New York for over a decade. Born in the U.S. to Maltese parents, the filmmaker recalls formative years of seeing amazing films “connected to a cultural context.” “I thought every single country was making these films except for Malta. I naively imagined it would happen to Malta when the digital revolution came around. Cameras were cheap, editing software was accessible, but films still weren’t being made. I think there was something bigger missing. I just kept dreaming about making stories in Malta.”

On working with local Maltese crews on his films, Camilleri said “the crews understood that they were working on something they could be proud of in a different way. This was a project to share with our families, to connect us deeper to our community, something in our language, with faces that resemble ours on screen. I need that energy because these films are extremely hard to make.”

“People worked incredibly hard on ‘Gladiator 2,’ of course, but they worked even harder on my film, and they’re ready to do it because they perceive that there’s something more than what those films can offer, with all due respect to Sir Ridley.”

Rebecca Cremona, whose 2014 drama “Simshar” was Malta’s first-ever Oscar submission for the best international feature category, says she would like to see a “more cohesive ecosystem between the incentive for servicing and investment into local productions.” The filmmaker is currently on the board of the Malta Producers Association, and says that one of their main goals is that “revenue coming in from the big blockbusters attracted by the 40% incentive feeds into our burgeoning film industry.”

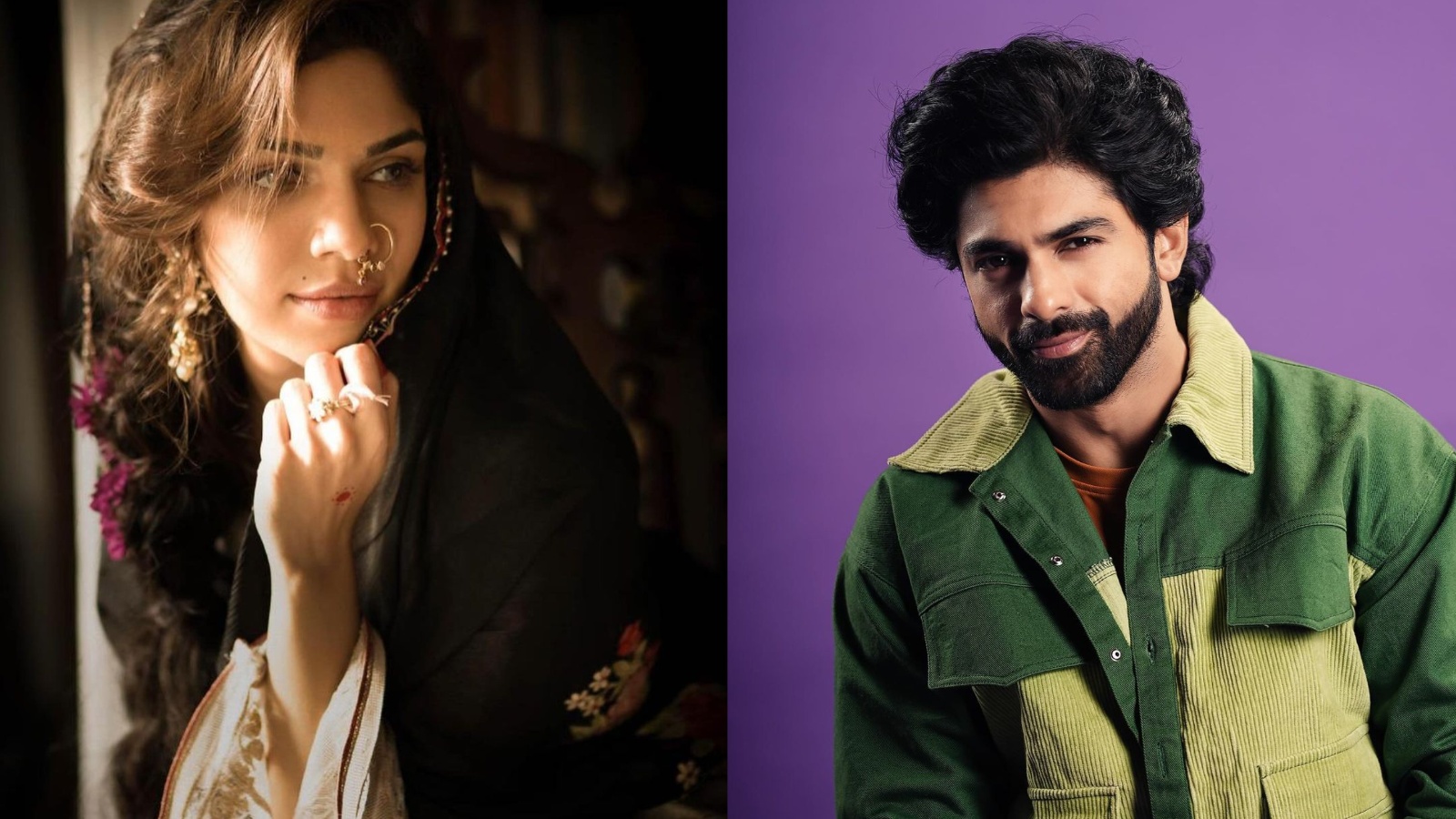

Xelter

Courtesy of Film Bridge International

Cremona is one of the many Maltese film professionals who started their career as a trainee in major international productions, having worked on the set of Steven Spielberg’s “Munich” and Alejandro Amenábar’s “Agora.” She said the experience helped her “in exposing me to a way of filmmaking that is extremely rigorous and high-end within mainstream Hollywood, but also in terms of people I got to know. I became friends with this Hungarian trainee who, fifteen years later, went on to direct ‘Son of Saul.’ The world is large but it is also small.”

Speaking on the identity of Malta’s national cinema, Cremona added that Maltese cinema is “not recognisable.” “When someone tells you about a French or a Polish film, you get an instant idea of what it is. When one tells you about a Maltese film, very few people can picture what that is. There is a beauty in creating something while free from the shackles of tradition but, on the other hand, you have to build everything from the ground up.”

Martin Bonnici, the director of the political thriller “A Vipers’ Pit,” said that this undefined national identity is one of the reasons distributors struggle to market Maltese films. With his next project, horror film “Xelter,” Bonnici hopes to bypass this issue by tapping directly into the genre market. “Xelter” is an American-Maltese co-production including The De Laurentiis Company (“Hannibal”) and Head Gear Films (“Talk To Me”). Film Bridge International launched sales on the film AFM late last year.

“Genre works. It sells. Even from the teaser trailer, there has been noted interest because it is a strong genre offering and it doesn’t look like other genre films. The idea with ‘Xelter’ was to create a classic genre film that is still selling our culture. The main monster in the film is called the Babaw and it’s a shadow monster similar to the boogeyman, but one that Maltese people grew up with.”

When commenting on the opportunities presented by working within a young national cinema, all filmmakers pointed out the need to establish strong connections with neighboring countries that share low-capacity film industries. “We need to stop looking at the foreign element and embrace more of our local culture,” put Bonnici. “We are Semitic people as much as we are European. We are also Middle Eastern and North African by culture and need to shed our dependency on this Eurocentric understanding of who we are.”

“It is natural that there would be a collaboration with the wider Mediterranean, North Africa and the Middle East. We have a Semitic language, and a lot of our architecture is very Arabic,” concurs Cremona, with Azzopardi adding, “400 million people live in the Mediterranean region. Imagine we joined forces to create a funding pot between our countries. We must integrate the North of Africa and the Middle East and become the catalyst of this co-production hub where we can tell our stories for our own consumption.”

In the future, on top of creating a wider net of distribution between Mediterranean countries, Maltese filmmakers would like to be able to focus on getting their films seen by local audiences. “Ironically, given Malta’s size, how my films do internationally will always matter more. I would love for the opposite to be true,” says Camilleri, whose sophomore feature “Zejtune” is currently in post-production and eyeing a festival release in the first half of 2025.

“I think it’s vital to build audiences here and inspire future generations. Rome wasn’t built in a day. Hopefully, initiatives like the Mediterrane Film Festival will sustain an ongoing effort so we can develop local audiences, improve cinema literacy and create a desire for films like ‘Luzzu.’”

Luzzu

Courtesy of Kino Lorber