[ad_1]

CHICAGO — Bearded and bespectacled, YM Masood has a quiet nature that suggests he’s older than age 20. A political science major, he plans to graduate from college in December, well ahead of schedule. He’s studying for the LSAT, the entrance exam for law school.

He has another frequent role as well: protester.

Masood, a student at the University of Illinois Chicago, has taken to the city’s streets in recent months for pro-Palestinian rallies, often weekly and — once — twice in the same day.

“Palestine is definitely No. 1 right now,” Masood says. Last spring, he also traveled by train to support pro-Palestinian encampments at the University of Chicago and Northwestern and DePaul universities.

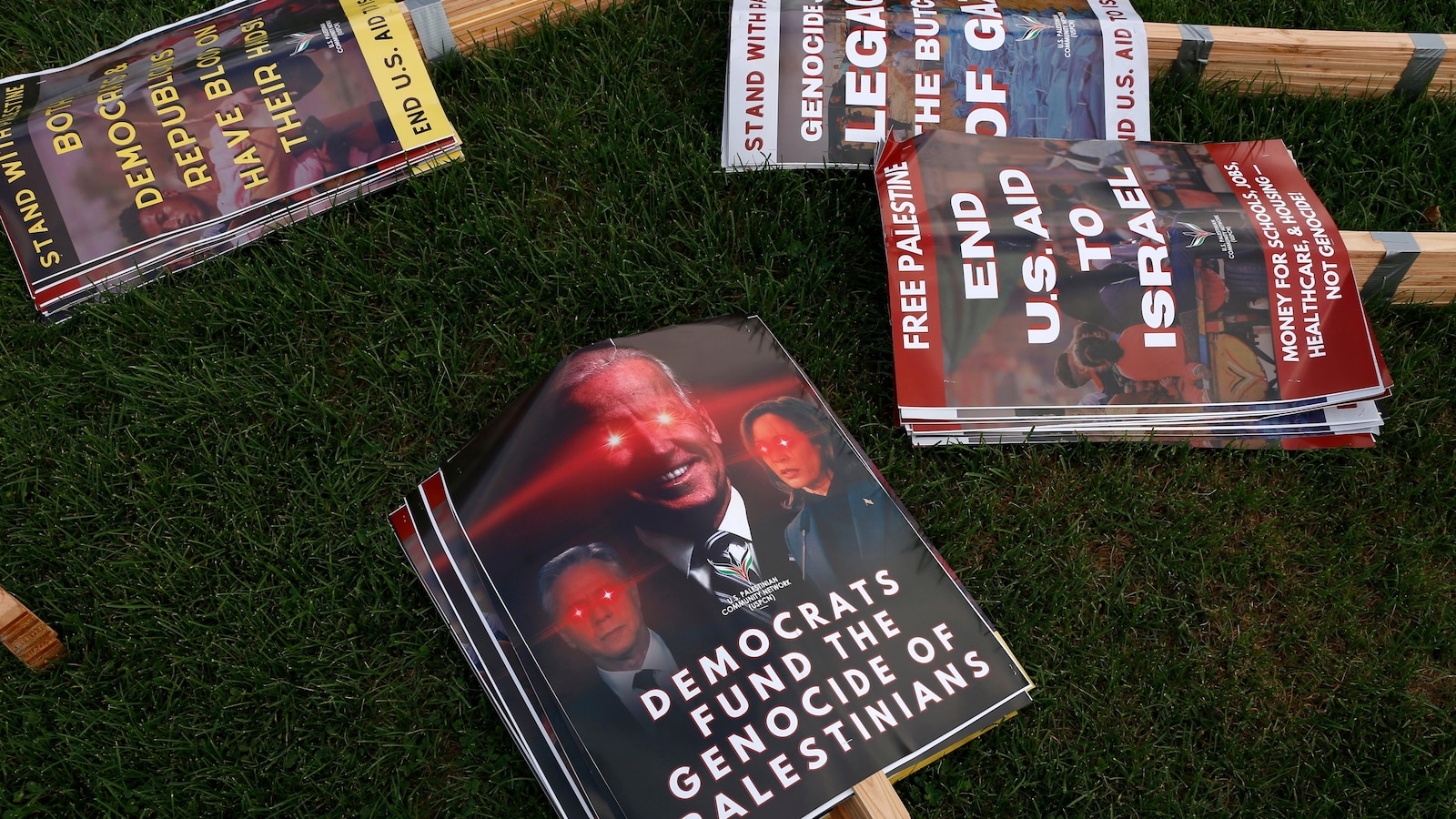

That set the stage for this week’s Democratic National Convention, where thousands gathered to raise their voices on issues from the Middle East conflict to abortion and immigrant rights. Though the cameras often focused on scraps with police, the overwhelming majority marched peacefully.

Masood was often there, volunteering as a marshal to help organizers of these larger protests keep things in line. The overarching messages to the Democratic Party and its nominee, Kamala Harris, were clear: End the war. Stop sending aid to Israel.

For Masood and other students, the war has become a lightning-rod issue for their generation, just as the Vietnam War was in the 1960s and South Africa’s apartheid system was in the 1980s.

Says Masood: “We’re not going to stand by while all these people are suffering.”

The death toll in Gaza recently surpassed 40,000. In Israel, about 1,200 people have been killed, and officials there say more than 100 Israeli hostages, including two small children, remain in Gaza.

The national Harvard Youth Poll conducted last spring found that 60% of college students and 64% of those who already had a college degree supported a permanent cease-fire in the Middle East. Among those surveyed, ages 18-29, a little over half said they sympathized with both the Palestinian people (56%) and Israelis (52%) — though they were less supportive of each of their governments and Hamas.

These protests, however, have continued to focus on the Palestinian people, as the war has destroyed huge numbers of homes and wiped out entire families.

“Before I got into activism, I was a lot more shy. …. But for me, this is personal,” says Masood, who is a Muslim of Indian descent. His father, an IT specialist, was born in Chicago. His mom, who teaches religious education, came to this country from India in the 1990s. Like his father, Masood was born in Chicago but grew up in a Detroit suburb until his family returned.

On campus, he’s known as the guy who drapes a red or black keffiyeh scarf around his shoulders. The Middle Eastern scarves have become an increasingly displayed symbol of solidarity with the Palestinian people. His own keffiyehs belonged to his father and to his late uncle, who also protested in support of Palestinians when they were young.

“I have this duty to carry on … what (my uncle) stood for and bring new meaning to it,” Masood says. He jokes that he wears the scarves so often that people wonder if he washes them.

Occasionally, he says, his parents see him on TV at protests with groups such as Students for Justice in Palestine and Students for a Democratic Society. Mostly, they don’t want him to do anything “reckless” that would jeopardize his future. He promises them he won’t and walks a fine line between his activism and that future — law school and a job, for instance. It’s a valid concern, since some college students who’ve gone public with views on the Hamas-Israel war have lost employment offers or been harassed online.

“My parents … they’re kind of worried about me,” Masood says. “But I feel like at this point, they realize that I also, like, have a duty to do. And they’re not totally against it.”

If he were to get arrested, he concedes, that would likely change.

On a breezy summer day just before the DNC, Masood sat on the grass with a small group, painting protest signs at a park on Chicago’s South Side.

One recent college graduate complained about her parents’ “weird liberal logic.” When Democrat friends were coming over, she said, they asked her to take down a painted sheet she’d hung out her bedroom window decrying what she and many others call a genocide in Gaza. “They didn’t want it to be the focus of conversation,” she sighed. During the DNC, she put the pro-Palestinian message back up with a “Harris-Walz” sign near another window.

Next to her, a man in his early 30s said he planned to agitate police officers guarding the DNC, his sentiments seeming to echo anti-Vietnam riots at Chicago’s 1968 DNC. He painted his hands red and pressed them onto poster board, scrawling the words, “America Has Its Hands Covered In Blood.”

There were a few renegade groups at the DNC. One briefly breached an outer security wall, leading to 13 arrests. Dozens more were arrested the second night outside the Israeli consulate.

As a volunteer marshal at the larger March on DNC protests, Masood’s role was quite the opposite of agitation. As they were trained to do by organizers, marshals work to minimize conflict with police and counterprotesters.

“We don’t usually organize disruptions,” Masood says.

Why were the protesters were so focused on Democrats, even as the Biden administration continued to push a cease-fire in the Middle East? At the DNC protests, the answer was clear: Many protesters feel the president has not done enough to help Palestinians, and they fear Harris would continue to fund Israel.

“I feel like the Democratic and Republican parties are two of the same parties that just say things differently,” Masood says. “They’re controlled by corporate interests, and they won’t benefit the average person.”

This is the first presidential election for which he’ll be old enough to vote, but he’s not excited. He plans to vote for Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein. While ending the war in Gaza is his top issue, he lists others of importance — abortion rights, immigration and climate change, among them.

But he says his generation feels overloaded.

“We would have loved to live in a world where all we would have had to worry about was us and our families and our education,” he says. “But that isn’t the world we live in at the moment.”

On peace in the Middle East, Rania Batrice, a Democratic political strategist who was Bernie Sanders’ deputy campaign manager during his 2016 presidential bid — and who is Palestinian American — said she is “cautiously optimistic” with Kamala Harris as the Democratic nominee.

“We now have somebody at the top of the ticket who, at minimum, at least has used empathetic language,” Batrice says. “She was the first person in the administration to utter the words ‘cease-fire.’” The shift in rhetoric, Batrice says, “is a very, very welcome change. It’s also not enough.”

For that reason, Batrice, who came to Chicago for the DNC, wholeheartedly supported the March on DNC events in which Masood participated.

“I think peaceful protest is not only a longstanding tradition in this country,” she says. “It’s also how we’ve seen — over and over and over again — policy shifts happen.”

At the mass protest on the DNC’s first day, Masood was among the first to arrive to help with setup, hours before the march began. The scene morphed into a mish-mash of humanity, as pro-Palestinian protesters from across the country and journalists from around the world poured into Union Park.

A group with Israeli flags showed up at one point, circling the park as protest marshals in fluorescent vests scrambled to create a human barrier to fend off potential conflict. Nearby, a man with a guitar sang Christian music, including “Amazing Grace,” for hours.

Across the street, another man with a fire-and-brimstone message used a loudspeaker to taunt the much larger group in the park. “You’re all terrorists!” he shouted, also saying he supported Donald Trump.

Masood paid him little mind. His own faith, he says, is about love and compassion. “Eventually, you just learn to ignore them. Screaming back if they’re screaming at you, you’re only going to endanger yourself and endanger others.”

As the sea of humanity, numbering thousands, walked a 2-mile (3.2-kilometer) route to another park and back, people banged on drums and waved signs. Masood and fellow marshals used hand signals to keep themselves interspersed on either side of the protest route. Police marched alongside, using bicycles to create rolling barriers to help keep things contained.

Masood felt the message was heard. He pronounced himself “energized.” He realizes Stein and the Green Party aren’t considered contenders for the presidency. But his first presidential vote is a protest, too.

Whoever wins, Masood says, “We’ll be out here in the streets, like how we were today, no matter if it’s Democrat or Republican. We will always be protesting for the people.”

___

Martha Irvine, an AP national writer and visual journalist, can be reached at mirvine@ap.org or at http://twitter.com/irvineap.

[ad_2]