[ad_1]

AURORA, Colo. — Starting seventh grade at her first American school, facing classes taught entirely in English, Alisson Ramirez steeled herself for rejection and months of feeling lost.

“I was nervous that people would ask me things and I wouldn’t know how to answer,” the Venezuelan teen says. “And I would be ashamed to answer in Spanish.”

But it wasn’t quite what she expected. On her first day in Aurora Public Schools in Colorado this past August, many of her teachers translated their classes’ relevant vocabulary into Spanish and handed out written instructions in Spanish. Some teachers even asked questions such as “terminado?” or “preguntas?” — Are you done? Do you have questions? One promised to study more Spanish to better support Alisson.

“That made me feel better,” says Alisson, 13.

Outside the classrooms, it’s a different story. While that school system is striving to accommodate more than 3,000 new students mostly from Venezuela and Colombia, the city government has taken the opposite approach. City Council has tried to dissuade Venezuelan immigrants from moving to Aurora by vowing not to spend any money helping newcomers. Officials plan to investigate the nonprofits who helped migrants settle in the Denver suburb.

When Aurora’s mayor spread unfounded claims of Venezuelan gangs taking over an apartment complex there, former president and current GOP candidate Donald Trump magnified the claims at his campaign rallies, calling Aurora a “war zone.” Immigrants are “poisoning” schools in Aurora and elsewhere with disease, he has said. “They don’t even speak English.”

Trump has promised that Aurora, population 400,000, will be one of the first places he launches his program to deport migrants if he’s elected.

This is life as a newcomer to the United States in 2024, home of the “American dream” and conflicting ideas about who can achieve it. Migrants arriving in this polarized country find themselves bewildered by its divisions.

Many came looking for better lives for their families. Now, they question whether this is even a good place to raise their children.

Of course, it’s not always clear to Alisson’s family that they live in a discrete city called Aurora, with its own government and policies that differ from those of neighboring Denver and other suburbs. One thing has seemed obvious to her mother, Maria Angel Torres, 43, as she moves around Aurora and Denver looking for work or running errands: While some organizations and churches are eager to help, some people are deeply afraid of her and her family,

The fear first became apparent on a routine trip to the grocery store back in the spring. Torres was standing in line holding a jug of milk and other items when she moved a little too close to the young woman in front of her. The woman — a teen who spoke Spanish with an American accent — told Torres to keep her distance.

“It was humiliating,” says Torres. “I don’t look like a threat. But people here act like they feel terrorized.”

And when Aurora Mayor Mike Coffman — and then Trump — started talking about Venezuelan gangs taking over an apartment and the entire city of Aurora, Torres didn’t understand. While she didn’t believe that gangs had “taken over,” she worried that any bad press about Venezuelans would affect her and her family.

Keeping out dangerous people is important to Torres. The whole reason her family left Venezuela was to escape lawlessness and violence. They didn’t want it to follow them here.

In addition to Alisson, Torres has an older daughter — Gabriela Ramirez, 27. Ramirez’s partner, Ronexi Bocaranda, 37, owned a food truck selling hot dogs and hamburgers. Bocaranda says government workers in Venezuela extorted a bribe from him known as a “vacuna,” or vaccine, because paying it ensures protection from harassment. He paid them the equivalent of $500, about half a week’s earnings, to continue operating.

The next week, when Bocaranda refused to pay, the government workers stabbed him in the bicep; the one-inch scar remains visible on his left arm. The men threatened to kill Ramirez and her young son, who were both at the food truck that day. Bocaranda sold the business, and the family, including Torres and Alisson, all fled to Colombia.

A little over two years later, the family headed north on foot through the Darién Gap. In Mexico, they crossed the border in Juarez and turned themselves in to U.S. Border Patrol. They all have deportation hearings in 2025, where they will have the opportunity to plead their case for asylum based on the threats against Bocaranda, Ramirez and her son. In the meantime, they have settled in Aurora, after hearing about the Denver area from a family who helped them on their journey to the U.S.

Torres and her daughter tried to get their kids into school soon after they arrived in Aurora in February, but they were confused by the vaccination requirements. Could the kids enter school with the vaccinations they received in Venezuela and Colombia, or would they have to get all new shots? Would they have to pay for each one, potentially costing hundreds of dollars per child?

Alisson and Dylan stayed home for months. Dylan played math or first-person shooter games. Alisson watched crafting videos on TikTok. When they finally entered school in the fall, Gabriela Ramirez and Torres both hoped instruction would be in English, believing their children would learn the language faster that way.

If they’d arrived in Aurora, say, three years ago, that might have been what they encountered.

Aurora is accustomed to educating immigrants’ children. More than a third of residents speak a language other than English at home, according to the 2020 U.S. Census. Immigrants and refugees have been attracted to Aurora’s proximity to Denver and its relatively lower cost of living.

But the sudden arrival of so many students from Venezuela and Colombia who didn’t speak English caught some Aurora schools off guard. Before, a teacher in the 38,000-student school system might have had one or two newcomer students in her class. Now, teachers in some schools have as many as 10, or a third of their classroom roster.

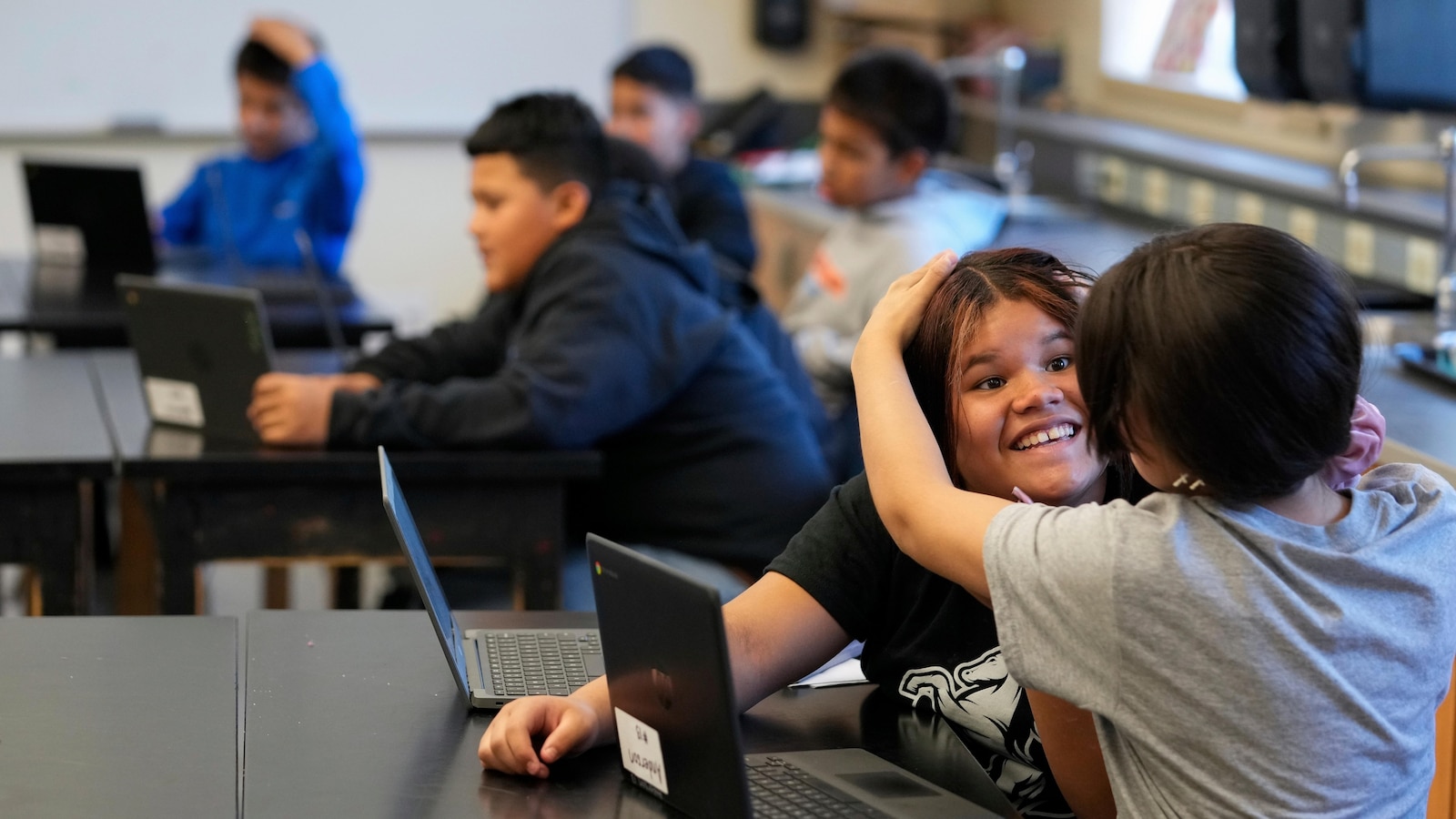

When Marcella Garcia visited classrooms where only English was spoken, she noticed the newcomers weren’t talking. “Kids were being left out and not able to engage,” says Garcia, principal at Aurora Hills Middle School.

The schools reached out for advice and training from the district’s central office, which recommended a strategy called “translanguaging.” That means using Spanish at times to help students make meaning of the English lessons and conversations happening around them.

It’s not clear how much it’s helping students learn — it’s too soon to tell — or if the school is striking the right balance between translating for newcomers and forcing them to engage in what teachers call a “friendly struggle” to understand and learn English.

But the approach has helped Alisson feel more at ease. On her first day of school, her social studies teacher, a bald man with tattooed forearms and a gruff teaching persona, didn’t translate anything or use Spanish in his presentation. “I thought about sitting there and not saying anything,” Alisson remembers. “But then I thought, ‘I’m here to learn.’”

She and a friend approached the teacher during class. Now Jake Emerson is one of her favorite teachers.

On a Wednesday in September, Alisson and her friends were sitting at a round table in the back of Emerson’s class. They spoke Spanish among themselves as Emerson spoke to the rest of the class about the drawing he was projecting on the large screen in the front of the class.

It was a scene from an ancient Egyptian marketplace. “What do you think this dude here is doing with the basket?” Emerson asked the class. The students at Alisson’s table kept talking, even as Emerson spoke. One girl who’d been in Aurora schools longer than the rest translated for Alisson and the other teens.

Before the school adopted this new approach, teachers may have shut down a conversation among students in Spanish. “If I saw two students speaking Spanish, I assumed they were off topic,” says Assistant Principal John Buch. Now, he says students are encouraged to help each other in any language they can.

So far, there appears to be little public pushback in the district against this approach. It generally requires more work for teachers, who have to translate materials or their own speech in real time.

While teachers try out new Spanish vocabulary, English-speaking students show a range of responses. Some seem bored or annoyed by their teachers’ sudden interest in speaking Spanish in class. Bilingual students appear proud when they can help teachers trying to use more Spanish in class.

Still, some English-speaking and bilingual students have harassed Alisson. A few weeks after school started, a group of boys tried to stop her from sitting in her seat in class. They called her ugly and told her to go back to her country. When Alisson reported this to a teacher, nothing changed. “They say they don’t tolerate bullying,” she says. “But this is bullying.” Weeks later, the boys eventually stopped.

After spending most of the day in mainstream classes, Alisson and her newcomer peers let loose in a class called Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Education. It’s the only class explicitly designed to help new immigrants speak English.

The teacher, Melissa Wesdyk, does not speak fluent Spanish. She recently started using Google Translate at times, as a simultaneous interpreter. She speaks her instructions into her laptop, and a slightly robotic voice says the instructions in Spanish.

The same is not available in Amharic or Farsi, languages spoken by two of the more than two dozen students in the class. For those two, she translates the instructions in writing and projects the words on a screen in the front of the room.

Wesdyk rarely smiles and remains serious as she runs the class. Perhaps that’s because the students are far more unruly than in Alisson’s others. Wesdyk acknowledges the relative chaos, but says it’s because the Spanish-speaking students are more comfortable in a class that’s almost exclusively Latin American immigrants.

One boy keeps standing on his chair during the lesson, and Wesdyk stops class at least four times to redirect him. “Por qué hablas?” she asks him. Why are you talking? Another time she says, “I need you to stop.”

The course also demands more of the students, whom Wesdyk presses into pronouncing words in unison and answering questions. It’s hard work, and her methods don’t always hit their mark.

Toward the end of the class, Wesdyk tells the class they are going to do a “whipshare.” Google doesn’t know how to translate that, so it just repeats the word in English. Each student is to share one of the words they wrote earlier, when the class was identifying English words for each letter of the alphabet.

When Alisson offers the word “pink” for the letter P, Wesdyk appears surprised and a little flustered. “That’s not one of the words I wrote down, but good word.”

For the letter F, another boy says “flor,” as in Spanish for flower. To observers, he seems to be trying to say “flower,” but mispronouncing it. Wesdyk doesn’t appear to understand. “Floor?” she says back to him. The boy repeats “flor,” and Wesdyk says, “Floor?” emphasizing the English R sound. The boy looks embarrassed.

In mid-September, Alisson’s mother receives messages from Aurora Public Schools that there have been rumors of bomb threats at its schools and others across the state. It’s not clear if the threats are related to Trump’s rhetoric about Venezuelan gangs taking over Aurora. After all, similar problems ensued after his false comments about pet-eating Haitians in Springfield, Ohio.

The school system’s messages say there is no truth to the bomb threat rumors, but that doesn’t make Torres and Alisson feel better. Torres still sends Allison to school, despite her fear. She’s learned she can get in trouble if Alisson misses class without a good excuse, and Alisson is generally happy at school.

But neither of them understands how American schools and children could become a target, even if it’s just a rumor.

“This doesn’t happen in my country,” says Torres.

Venezuela’s economy and democracy may be in shambles, says Torres, but no one there would think of threatening children at school.

___

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.